Engravers for The London News 1800s and 1900s [View all]

I came across copies of The London News online and the engravings in it are just astounding for the artistry. I looked up some information on the engravers.

You can view issues of the London News here

https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/000520935

https://www.iln.org.uk/iln_years/earlyhistiln.htm

ILLUSTRATIONS OF NEWS EVENTS

Illustrations of news events had been published in newspapers from time to time before the ILN's advent but not as a regular feature. The Weekly Chronicle, which fostered sensational pictures, went to town in 1837 when Hannah Brown was murdered by James Greenacre, whose trial at Newgate with its many gruesome details provided ample material for engravings in six consecutive issues.

Plans for launching the illustrated newspaper were now being organised and Ingram became friendly with a young man named Henry Vizetelly who, with his elder brother, had an engraving and publishing business near to Crane Court. Vizetelly, a wood engraver, was already associated with others who engraved illustrations for books, and he knew many versatile artists including A. Crowquill, Kenny Meadows, "Phiz", and Leech, who were making drawings for Punch, then only recently founded in July 1841.

THE FIRST ILLUSTRATED NEWSPAPER

By then The Illustrated London News had been well and truly established as the world's first illustrated newspaper, the forerunner of the French L'lllustration and Le Monde Illustre; Germany's Illustrierte Zeitung; Amsterdam's Hollandsche Illustratie; America's Leslie's Weekly (started by one Harry Carter from Ipswich, Suffolk - he had worked previously for the ILN in charge of engraving for 6 years) and Harper's Weekly; The Graphic; The Sphere, Gleason's Pictorial Drawing -Room Companion (Boston, USA) and scores of other well known weekly and daily picture papers including in recent years Life and Paris Match.

Arriving at the stairs, you went up to the first floor and joined a motley crowd of authors, artists, engravers and personal friends of Ingram. He was full of excellent ideas, determined to carry them through at all costs and would silence objections with a vigorous thump of his fist on the table. His pluck and enthusiasm were infectious and everyone worked with a will to get the paper out in time. Artists and engravers often worked sixteen hours a day, and sometimes thirty-six hours at a stretch with only a few snatches for meals, and an occasional halfhour's rest on the floor.

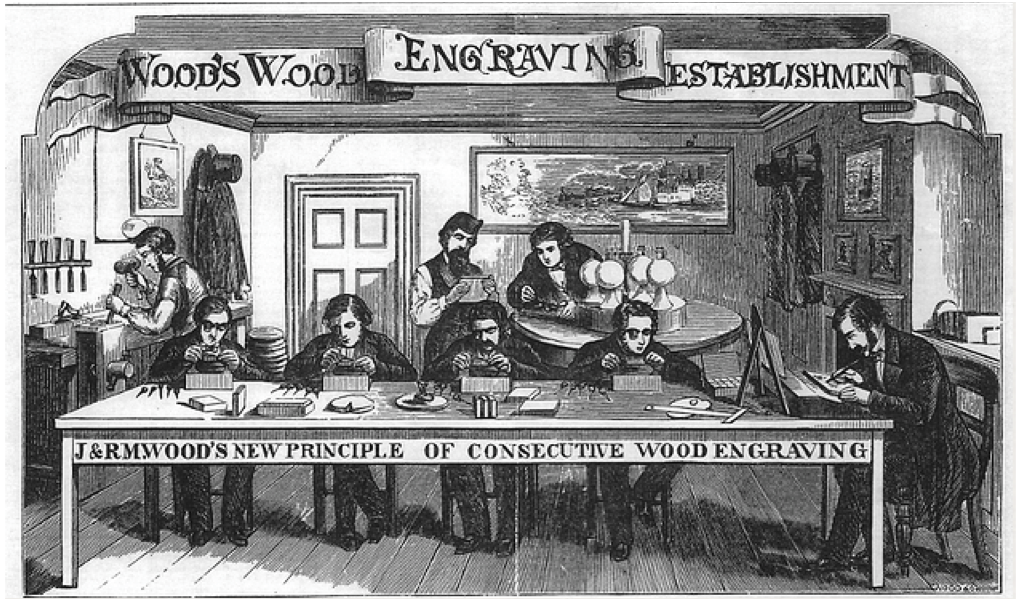

Wood engravers working for the ILN included Ebenezer Landells (1808-1860), and William Harvey (1796-1866) each having been pupils of the famous Thomas Bewick (173-1828). Landells, artist and engraver, had a large staff of assistants and pupils and the signature "Landells" in small letters appears below many of the engravings. Pictures signed "S. Sly" were engraved by members of Stephen Sly's firm in Bouverie Street, just off Fleet Street. Other engravers included WJ Linton and Orn Smith.

One of the reasons for moving the ILN to 198 Strand was to get accommodation where its own staff engravers could work- "We shall be able to keep our wood engraving department further in advance by the retention of permanent artists ready at a moment's notice for the contingencies of every public event".

Wood for the engravings came from the box tree whose close-grained trunk grew to about seven inches in diameter. Slices sawn across the trunk had the bark removed and were cut into rectangles, the edges squared up and the surface made smooth for the artist's pencil. These blocks, about five inches wide, were then available for engraving.

THE ENGRAVER'S ART

When an illustration was to occupy a page, or double-page or even a larger space, the small blocks were drilled and channelled underneath for the insertion of brass bolts and nuts which gripped the pieces of wood together "without line, speck or flaw", thus making a printing surface of the size required. If a large illustration had been drawn on the surface of six blocks bolted together, the pieces could be unbolted and distributed to six engravers and when their work was finished the pieces would be bolted up again, thus saving much time.

How did these remarkable craftsmen, the wood engravers, work - The block, which was steadied by the thumb and fingers of the left hand, lay on top of a leather bag filled with sand. During daylight hours, the bag rested on a bench close to a window, but at night, an oil or gas lamp provided illumination. The engraver's head, with a watchmaker's magnifying glass clipped to one eye, would be bent down near to the block while the thumb and fingers of the right hand gently pushed the sharp front edge of the cutting tool - the graver - to shave away narrow slivers of wood so as to leave whites and tints between the darker lines of the picture.

If we look through a magnifying glass at these magnificent wood-cuts, we must marvel at the skill and patience of those wood engravers and regret that such artistic craftsmanship is now almost lost for ever.

Close up of an engraving